The future of DTC ecommerce is hard. And only getting harder.

Low customer acquisition costs, low CPMs on Facebook, low competition. Much of what led the original digitally native darlings to IPO and become large businesses no longer exists.

Today, the pitfalls surrounding global supply chain disruption are deepening. It’s the same with macroeconomic factors like inflation as well as environmental concerns like packaging waste.

Add to that the VC dollars propping up DTC, the return to in-store shopping, and the emergence of retail curators — white-label “start-ups” that feel just like DTC. Together, they signal one thing …

For ecommerce brands, operational strategy is no longer a luxury.

The ability to attract, retain, and scale talent has always been a competitive advantage. As more waves slam into the DTC landscape, that reality will only become more true. Your people will become your “moat.”

So, how do you develop operational leadership? It starts with understanding and then navigating three tensions: (1) vision, (2) meaning, and (3) balance.

1. Vision: Important Versus Interesting

The bigger you get, the more specific your vision needs to be.

Naturally, successful businesses have layers. The further down you go, the more complexity and nuance emerge:

- Company mission and values

- Brand planning and strategy for big ideas

- Campaigns aligned with your marketing calendar

- Metrics and KPIs to govern initiatives, teams, and individuals

Growth inevitably diversifies your organization as well. Particularly, diversity of thought, personality types, and motivational fuel.

When you’re small, you tend to attract people who think like you.

In that setting, you can leave a lot up to assumptions and “mind-meld” moments. If you’re extroverted and talk fast, you might easily inspire the people on your team. If you’re analytical, so too are those who gather around you.

Size ends that. What’s more, as you get further away from employees, misunderstandings multiply.

The problem isn’t that people aren’t willing to take hills. It’s that, without a clear vision, they’ll take the wrong hills.

Early on in my career, I’d look around, see something not happening, assume that meant nothing was happening, and then go do something to fix it.

It didn’t matter to me whether I should have gone to fix it.

As a leader, you need to be very specific and intentional about what to focus on because high performers are people who are ambitious and want to be doing.

The intentions are good, but as you get bigger, it is not possible to be everywhere to know everything. That level of transparency simply doesn’t exist in large organizations.

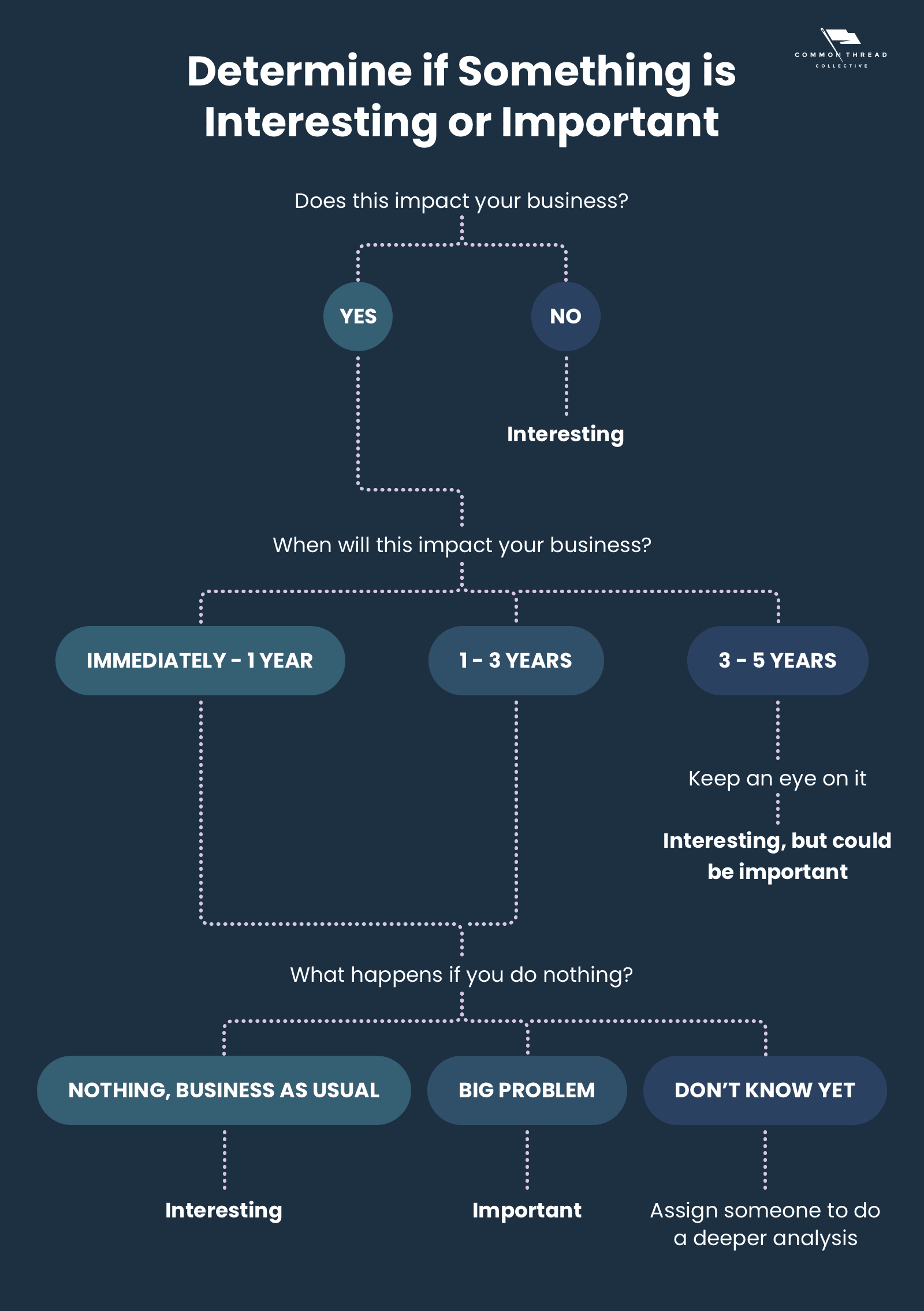

Instead, it’s about separating important from interesting. To help, I’ve create a flowchart of the kinds of questions you can ask yourself when new ideas or projects come to mind:

Even more crucial, there’s a difference between defining success for yourself and enabling success through others. If you protect your team from all of the angst of getting there, they’ll never learn.

Nor will they thrive.

Clarifying your vision by separating what’s important from what’s interesting is good. Guiding your team to develop their ability to make distinctions is even better. Likewise with the next tension.

2. Meaning: Effort Versus Impact

Once you’ve nailed down your specific vision, you must answer three fundamental questions:

- What is your objective?

- What is your desired outcome?

- What needs to happen in the next year?

Your answers to these questions act as a ladder for analytical teams — marketing, media buyers, supply chain or logistics — to climb in order to achieve your vision.

But for soft-skill roles — jobs less connected to obvious financial outcomes — how does their work connect with the overarching goal?

Let me be blunt. If someone doesn’t see the impact of their work, they will ask, “Why am I even doing this?”

It’s a question I’ve been thinking about recently. Maybe it’s a midlife crisis. Maybe it’s a COVID effect. Regardless of the cause, it speaks to a deeper need we all have.

The idea of effort versus impact. Or, effort-to-impact ratio.

Effort: noun, eh-fert; (1) an exertion of physical, mental, or emotional energy; (2) the amount of energy expended to get your desired result

Impact: noun, im-pakt; (1) the outcomes and results from your work, can be positive, effective, and worthwhile; (2) the personal or professional feeling of accomplishment and achievement

Everything in high-growth organizations feels high effort, often with seemingly minimal impact.

In a remote world where people are one of the few remaining competitive advantages, you have to get wide-eyed that we’re all at-will employees.

We can go wherever we want. We can do whatever we want. Especially when we’re surrounded by really smart people.

People choose where to work to be part of the mission. When they feel like their work does not contribute to the health of the business, they’re going to disengage.

How do you scale your impact? How do you scale someone else’s impact?

Typically, the answer is some combination of giving them a team, a better title, and more money. But that’s not the whole answer. The problem is two-fold.

First, as individual contributors move into management, what got them there will not get them to the next level. In fact, the very skills that made them successful as individuals can be their undoing as leaders.

Second, title and ego are different animals. Someone’s title might be X, but their ego says, “I want to be consulted and actively making important decisions that impact the organization.”

Acknowledging these two factors forces us to ask, “What does having a meaningful relationship with your job look like?”

For the individual contributor turned manager, a meaningful relationship might be the ability to mentor and develop talent into the field where they’re an expert. They also might have a couple of side projects that they can entirely own.

For the title with the mismatched ego, many large companies use title as a shorthand way to understand how to engage with someone. You may be incredibly talented and intelligent, but people may discount it because you don’t have a senior enough role. Mitigating this involves building a culture of openness and allowing employees, no matter their title, to provide input and to be heard.

My entire career has been at large, international companies. I get to do what I love and I’m highly competitive. If my effort is constant, then what needs to be true for my impact to change? For me, it was moving to an organization where the same level of effort will yield higher impact.

Making that decision didn’t come easy. It meant getting honest and ultimately rejecting the third and final tension.

3. Balance: Work Versus Life

I’ll be honest, the phrase “work-life balance” stresses me out.

Why? Because it creates a false expectation.

When you think about balance, you think 50:50. And your mind creates a delineation between your work and your personal life.

In reality, it’s not 50:50 — it’s all kind of mixed together. It was already mixed together before COVID, but COVID exacerbated it. We weren’t really working from home; we were at home during a pandemic trying to work. (We probably all need some sort of therapy.)

The stress of achieving work-life balance comes from a forced delineation: to be completely logged off at certain times, and be completely logged back in at others. Four hours here, so I need to do four hours there.

I derive a lot of my self-worth from the work that I do. I also get a lot of energy from my work. If I were to reject that or say, “That’s wrong,” it’d be impossible. That is just how I’m wired.

Trying to delineate personal passions from work passions caused me to strive for a false ideal that I just don’t think exists.

That’s why I reject the idea of work-life balance.

Far better would be to use a framework like my friend Kat Cole’s “Values, Money, Ego, and Capabilities.” As part of a larger exercise, her questions on finances, ego and affiliation, and capabilities have been foundational for me. (Special thank you to Kat for letting me adapt it here.)

‘Architect’ Your Work & Career Choices: 3 Columns

1. Financial

Where are you: income, expenses, liquidity, assets broadly? What are your needs? Can they be met? If so, what’s your wiggle room or cushion? If not, what do you need to meet those needs?

2. Ego & Affiliations

What matters to you that makes you feel proud about a role, a company, a body of work? Consider the elements that are often tied to external descriptions: mission, title, size, reputation, etc.

3. Capabilities

What are your most valuable skills (Capabilities A)? What skills do you want to develop (Capabilities B)? For both types, examine your assumptions. The ideal mix varies by person and by the season they are in, but most need some mix of both to thrive.

Answer each question independently — only focus on that topic — by addressing each checkbox below. Click to enlarge image.

I’m always going to give 110% because that’s how I’m wired. So it’s actually much better if I just continue to do 110%. I have to choose to love myself and accept myself for all of the great pieces of me and all the flaws.

Operations Is About One Thing & It’s Not a ‘Thing’

Yes, the future of DTC is uncertain. It’s hard and getting harder.

Maybe these three operational tensions took a more introspective turn than you expected. But that’s the point.

The winners of this next season will look different from the original DNVBs. If you can’t outspend the competition, you have to outsmart them. You also have to out talent them.

By navigating important versus interesting, effort versus impact, and work versus life … you’ll place one of the few remaining moats at the center of your business: people.

The journey won’t be easy.

But I’m so excited to be traveling alongside you.